Time to Update Iowa's Water Plan

posted

by Michael Schmidt on Tuesday, July 1, 2025

This blog comes from Jerry Anderson, Richard M. and Anita Calkins Distinguished Professor of Law at Drake Law School, and Michael Schmidt, General Counsel for the Iowa Environmental Council and Chair of the ISBA Environmental and Natural Resource Law Section.

Iowa adopted a state water plan in 1985, but has not developed a comprehensive plan since then. The term “water plan” refers to the state’s system of regulating the use of its surface and groundwater resources. A state water plan should address all aspects of the water cycle, including precipitation, soil moisture, stream flow, and flooding. We focus here on one important aspect of a plan, groundwater management. Properly constructed and administered, the plan should provide the best approach to ensuring adequate supplies for the variety of domestic, agricultural, industrial and recreational uses of water. Although it focuses on water quantity, it also affects water quality.

Iowa has historically had little reason to worry about water quantity. Annual precipitation typically totals around 35 inches, much more than the Dakotas or Nebraska. Over much of the state, groundwater resources have also been capacious. The Jordan Aquifer, relied on heavily across the state, was once called “practically inexhaustible.”

Several factors now make those old assumptions unreliable:

- Extreme weather patterns. Drought and floods occur with more severity and frequency, exacerbated by climate change.

- Increasing water use. Although regional population growth is one driver, significant new users such as data centers also pressure existing systems. For example, data centers in the U.S. are projected to use between 1-1.5 trillion gallons of water by 2027, while bitcoin mining already consumes over 9 billion gallons of water annually. Each data center in Iowa may use hundreds of millions of gallons per year. The Meta data centers in Altoona reportedly can use up to 1 million gallons per day, while the Google facility in Council Bluffs uses 2.7 million gallons each day.

- Outside threats. Even if consumption in Iowa stays within our means, users in drier states increasingly consider interstate transportation of water to meet their needs.

- Pollution of water sources. The most recent Centers for Disease Control data show that Iowa ranks second nationwide in the number of new cancer cases, with almost 500 new cases of cancer per 100,000 people. Evidence increasingly suggests that nitrates or other chemicals in our drinking water might contribute to the problem. Emerging risks like PFAS or endocrine disruptors need to be addressed.

Current Iowa law requires the state to take measures to protect surface and groundwater sources “as necessary to ensure long-term availability in terms of quantity and quality to preserve the public health and welfare.” That broad admonition, however, has not been sufficiently implemented.

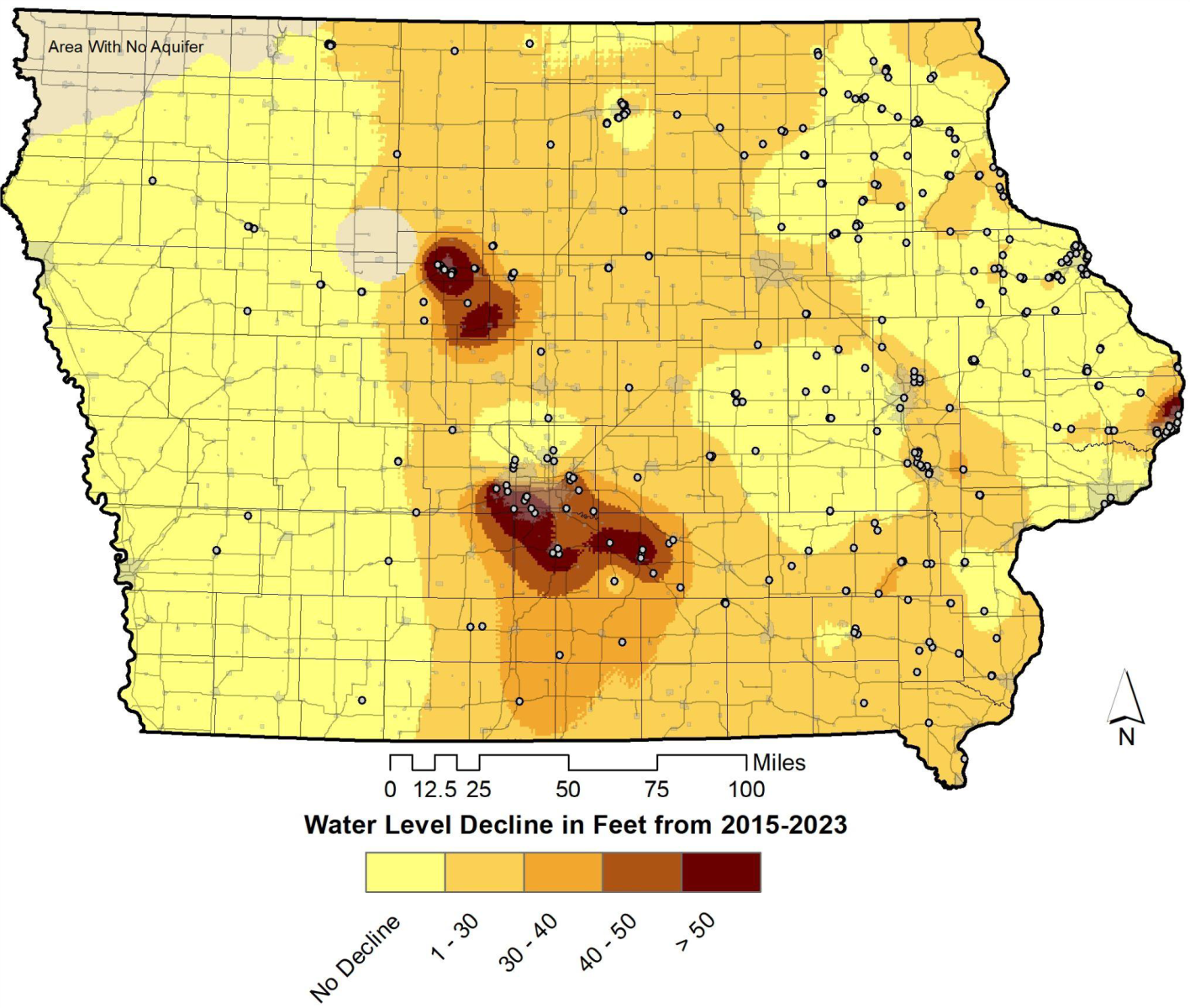

Groundwater levels have now begun to drop significantly in some areas of the state, which impacts both public and private wells. DNR has projected that total drawdown of the most widespread aquifer in the state, the Cambrian Ordovician aquifer, could exceed 200 feet in many areas over the 50-year period ending in 2029. Eighteen municipal wells across the Des Moines area rely on the Jordan Aquifer (the principal water-bearing unit of the Cambrian) to supply water, with an average annual drop in water level of eight feet per year since 2018. As shown below, the Jordan aquifer has declined recently across broad areas of the state.

Iowa has not engaged in comprehensive water planning for decades. Given the challenges outlined above, it is time to adopt a new plan. The elements of a revised water plan to help address these challenges might include:

1. Water allocation priorities. An Iowa Code provision and implementing regulation set out basic priorities among water users in the event of a water shortage. As you might expect, human consumptive uses take precedence over manufacturing use, which in turn takes priority over agricultural irrigation. However, those broad categories need additional refinement to help resolve the most difficult tradeoffs. Do we continue to supply the 34 data centers in Iowa, which each consume somewhere between 300,000 gallons and 1.25 million gallons of water per day for cooling? Should we prioritize a car wash or a golf course?

2. Conservation requirements. Currently, the law allows Iowa Department of Natural Resources little leeway regarding permits for withdrawal. For example, DNR can restrict industrial permits for Jordan aquifer withdrawals to 2000 gallons per minute, and cooling water must be used more than once. IDNR can impose some conservation requirements in water permits, but it would be beneficial to review their effectiveness and strengthen if necessary.

3. Mitigation. Many of the measures that could help recharge the aquifer, protect the water, and mitigate the impacts of weather extremes are currently beyond the state’s control.

In the 2023 Sackett decision, the U.S. Supreme Court significantly limited federal authority to prevent the destruction of wetlands, which slow down water runoff, filter pollutants, and facilitate groundwater recharge. While some states acted quickly to fill the void left by Sackett, Iowa has not.

Similarly, local officials are in charge of subdivision or zoning regulations that often impact groundwater recharge and water quality. Local ordinances could be amended to require or at least enable permeable pavements, water retention basins, or other practices to slow down runoff. A state comprehensive plan might support for these measures.

Iowa also places few restrictions on the increasing use of drainage tile, which cumulatively has a significant impact our water quality, downstream flooding, and aquifer recharge.

4. Groundwater contamination. Recent studies have found that many Iowa drinking water wells suffer from contamination by nitrates, bacteria, and PFAS. The Clean Water Act, however, only deals with point source pollution of surface water. The Safe Drinking Water Act focuses on public water supplies and provides limited authority to prevent activities that cause most groundwater contamination.

5. Out-of-state transfers. Although IDNR denied a recent application to withdraw millions of gallons of groundwater, to be transported by train to drought-stricken western states, the statute provides the agency with limited ability to deny future applications. The dormant Commerce Clause of the United States Constitution limits Iowa’s ability to discriminate against out-of-state consumers of our natural resources. However, nondiscriminatory restrictions that ensure adequate recharge would help limit transfers that unduly harm our water supply.

6. Resources. Statutory mandates will mean little if state agencies do not have sufficient resources to fully implement them. A quick review of IDNR’s staffing chart reflects a need to carefully consider how Iowa can assure more robust funding to adequately deal with this complex and crucial issue.

Iowa should not wait for another disaster before ensuring we do all we can to be prepared for the challenges ahead.