Report: Clean Water Act's Promises Half Kept at Half-Century Anniversary

posted

on Thursday, March 17, 2022

in

Water and Land News

Ninety-three percent of Iowa's 4,921 miles of assessed waterways are impaired for swimming and recreation

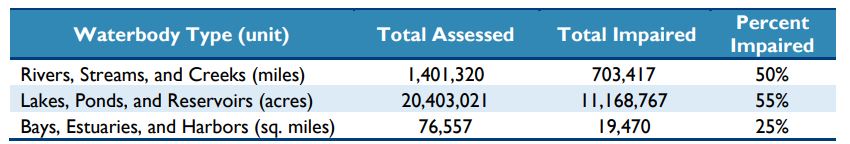

DES MOINES, IA -- A half century after the passage of the landmark federal Clean Water Act, and almost four decades after the law’s deadline for all waters across the U.S. to be “fishable and swimmable,” 50 percent of assessed river and stream miles – 703,417 miles nationally -- are so polluted they are classified as “impaired,” according to a new report by the Environmental Integrity Project (EIP).

Iowa is representative of many states with farm runoff problems, having 93 percent of its assessed river and stream miles impaired for swimming and water contact recreation (the fourth most in the U.S.) because of fecal bacteria and other contaminants, according to state data compiled for EIP’s report, The Clean Water Act at 50: Promises Half Kept at the Half Century Mark.

Iowa is representative of many states with farm runoff problems, having 93 percent of its assessed river and stream miles impaired for swimming and water contact recreation (the fourth most in the U.S.) because of fecal bacteria and other contaminants, according to state data compiled for EIP’s report, The Clean Water Act at 50: Promises Half Kept at the Half Century Mark.

Agriculture is the main driver of water pollution in Iowa. More than 30 million acres of the state, or over 85 percent, is farmland. The Hawkeye State is the leading pork-producing state in the nation, with the state’s 23 million pigs producing as much feces as 83 million people.

“The Clean Water Act is landmark legislation that has addressed industrial pollution in our nation’s waterways,” Alicia Vasto, the Water Program Associate Director for the Iowa Environmental Council, said. “However, agricultural states like Iowa suffer from the loophole that almost entirely exempts the agricultural industry from oversight. This has led to agriculture becoming the number one polluter of our nation’s waterbodies.”

“The Clean Water Act should be celebrated on its 50th birthday for making America’s waterways significantly cleaner,” said Eric Schaeffer, Executive Director of the Environmental Integrity Project (EIP) and former Director of Civil Enforcement at EPA. “However, we need more funding, stronger enforcement, and better control of farm runoff to clean up waters that are still polluted after half a century. Let’s give EPA and states the tools they need to finish the job – we owe that much to our children and to future generations.”

EIP’s report uses state data across the U.S. to also show that 55 percent of lake acres that have been studied and 25 percent of assessed bays and estuaries are impaired -- meaning they cannot be used safely for one or more public uses, such as swimming, fishing, or as sources of drinking water.

Table courtesy of Environmental Integrity Project. Source: The most recent available state Integrated Water Reports filed with EPA. Note: impairments include of waters assessed in the most recent cycle (six to 10 years, depending on the state), plus those assessed in earlier cycles.

One major problem, according to the report, is that EPA has neglected its duty under the federal Clean Water Act to periodically review and update technology-based limits for water pollution control systems used by industries. By 2022, two-thirds of EPA’s industry-specific water pollution limits have not been updated in more than three decades, despite the law’s mandate for reviews every five years to keep pace with advances in treatment technologies.

These badly outdated standards mean more pollution from oil refineries, chemical plants, slaughterhouses and other industries pouring into waterways than we would have if these standards had been updated on schedule.

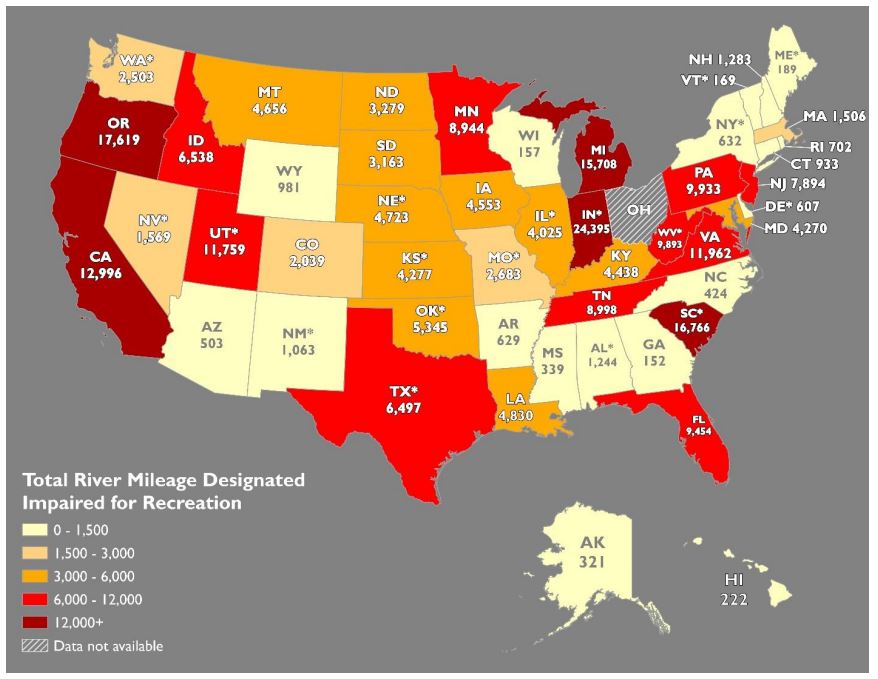

EIP’s report includes detailed maps and charts with the most recent available water pollution impairment data from all U.S. states. Among the state-specific findings of EIP’s study are the following:

- Iowa is representative of many states with farm runoff problems, having 93 percent of its assessed river and stream miles impaired for swimming and recreation (the fourth most in the U.S.) and 83 percent of its lake acres impaired for this (third most.)

- Louisiana ranks first for most estuaries classified as impaired for any use, with 5,574 square miles, or 92 percent of the waters assessed classified as impaired.

- Florida ranks first in the U.S. for total acres of lakes classified as impaired for swimming and aquatic life (873,340 acres), and second for total lake acres listed as impaired for any use (935,808 acres).

- California ranks first in the U.S. not only for the most total miles of rivers and streams impaired for drinking water. It also ranks third for river miles impaired for fish consumption (24,934 miles, or 33 percent of the miles assessed); and third in the U.S. for total acres of lakes impaired for swimming or any other use (800,053 acres, or 92 percent of the acres studied.)

- Indiana tops the list of states with the No. 1 most total miles of rivers and streams classified as impaired (or unusable) for swimming and water contact recreation (24,395 miles). (Ranked by percentage of miles assessed, Indiana ranks 11th. A full spreadsheet of all data for all states is available here.)

- Delaware has the highest percentage of its rivers and streams classified as impaired for any use, with 97 percent of the state’s 1,104 miles of assessed waterways listed as impaired for any use. Second most is New Jersey (95 percent) and third is Hawaii (91 percent).

The map below illustrates river and stream miles classified as impaired for swimming and water contact recreation by state.

States with asterisks reported usable data only for swimming and other primary water contact recreation impairments, not for secondary water contact recreation, such as kayaking. Ohio is not included because it does not count impairments like other states. Graphic courtesy of Environmental Integrity Project.

It is important to keep in mind that in some cases, states reporting higher levels of impairment may actually be doing a better job of monitoring waterways or are using more stringent criteria to assess water quality.

Although the most recent available state water quality reports to EPA make clear that about half of assessed river and stream miles and lake acres are impaired, the true extent of the nation’s water pollution is unknown because few states monitor all their waterways as required.

Due to limited funding and budget cuts, many state environmental agencies do not have the staff to test all their waters within mandated time periods – usually between six and 10 years, depending on state rules. For example, Missouri and Arkansas assessed only five percent of their river and stream miles in the most recent assessment period, according to EIP’s report. Across the U.S., 73 percent of rivers and stream miles were not studied during the most recent assessment cycle, and the same is true for 49 percent of lake acres and 24 percent of bay areas.

What can be done to close the gaps between the Clean Water Act’s lofty goals and reality?

The Clean Water Act at 50 report offers several solutions as the law’s half-century birthday approaches (the Act passed the U.S. House on an initial vote on March 29, 1972, and became law on Oct. 18, following votes by the Senate and House to override President Nixon’s veto.)

- EPA needs to do its job and comply with the Clean Water Act’s mandate for more frequent updates of technology-based limits for industry water pollution control systems. Despite a legal mandate for reviews of these discharge limits at least every five years, highly-polluting industries like chemical manufacturing have not had their standards updated since the 1970s – back when “modern” technology meant computers with floppy disks.

- Congress should strengthen the Clean Water Act by closing its loophole for agricultural runoff and other “non-point” sources of pollution, which are by far the largest sources of impairments in waterways across the U.S. Factory-style animal production has become an industry with a massive waste disposal problem and should be regulated like other large industries.

- EPA or Congress should impose more consistent, universal guidelines for waterway impairment designations for all 50 states, and for gauging unhealthy levels of key pollutants like nitrogen.

- Congress should make it easier to enforce key requirements of the Clean Water Act, including the cleanup plans -- called “Total Maximum Daily Loads” -- that are supposed to be one the primary mechanisms for reducing pollution.

- States are set to receive billions of dollars from Congress’ recent passage of a $1.2 trillion bipartisan Infrastructure Bill. Governors and lawmakers should, whenever possible, target this funding to water pollution control efforts, especially in lower-income communities of color that have long suffered disproportionately from pollution.

- Congress and states legislatures need to boost funding for the EPA and state environmental agency staff required to measure water quality, and to develop and implement the cleanup plans needed to bring impaired waterways back to life.

- Although achieving the Clean Water Act’s ultimate goal of 100 percent “fishable and swimmable” waterways will be hard, EPA should keep driving toward this target by setting interim national goals by decade and by creating enforceable plans to achieve these pollution reductions.

###

- cafos

- clean water

- clean water act

- harmful algal blooms

- microcystin

- nitrate pollution

- toxic algae

- water quality

- water recreation